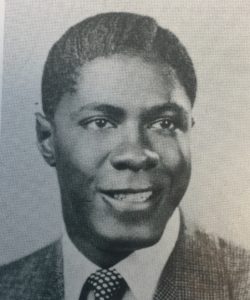

Clarence Benjamin Jones was born on January 8, 1931, at the height of the Great Depression in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His parents, Goldsborough Benjamin Jones and Mary Elizabeth Toliver, worked as domestic servants for Edgar and Eleonora Haines Lippincott, a wealthy Quaker family who lived in Riverton, New Jersey, approximately 10 miles north of Philadelphia on the Delaware River.

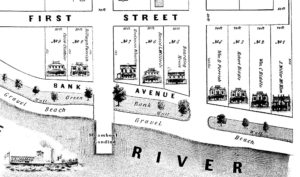

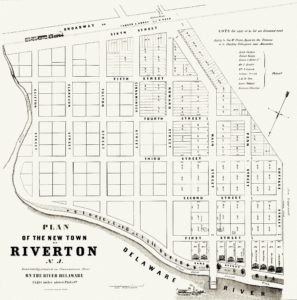

Riverton was founded in 1851 by a group of ten affluent Philadelphians, mainly Quakers, for summer homes for their families. They wanted a site offering country living with easy access to Philadelphia. The 120 acres of land purchased from Joseph Lippincott was one of the first totally planned residential subdivisions in the United States. It was a community for the elite. The Riverton Yacht Club was organized in 1865 and is now the oldest yacht club on the Delaware River and one of the oldest in the country. The Porch Club, a women’s club formed in 1890 and named for its informal meetings that took place on members’ porches, is one of the oldest in New Jersey. Riverton Country Club was founded in 1900. It is one of the earliest golf clubs in the country.

Isaac Clothier, son of one of the founders, Caleb Clothier, was a Riverton resident. He entered into a partnership with his friend, Justus Strawbridge, in 1862. They founded the distinguished department store Strawbridge & Clothier in Philadelphia. Joseph Campbell, for whom the soup company was named, lived in Riverton from 1872 until his death in 1900. Several members of the Dorrance family, who had partnered with and later taken over Campbell’s Soup, also lived in Riverton. The Hollingshead family had lived in Riverton for many years when their son, Richard, developed a “drive-in” movie. The world’s first drive-in theater opened June 6, 1933, in Camden, New Jersey. During the height of the Pennsylvania Railroad, many of its executives lived in or visited Riverton. These families had domestic servants; some lived with the families, but others lived in an area created specifically for African American domestic servants in Riverton and East Riverton.

In the late 1920s, Goldsborough was the gardener and driver for the Lippincott family, while Mary cooked, cleaned and cared for the Lippincott children. In 1931, at the age of 35, Mary gave birth to her one and only child, Clarence. Although Clarence was her pride and joy, it was necessary that Mary place him with family members or friends while she and her husband were live-in servants for the Lippincotts.

By the time of Clarence’s birth, while the United States as a whole experienced systemic, virulent racism, the Palmyra and Riverton communities worked towards racial unity. It was a microcosm of how Whites and Blacks could collaborate together, work and live together, and exist together humanely. The communities hadn’t eliminated racial tensions, but they were moving in a positive direction. By the 1940s, Blacks were business owners and community leaders. Albert Ricketts, who lived in East Riverton, became one of the first African American business owners when he began his construction company, Ricketts & Sons. Many of the commercial structures and homes in East Riverton and Palmyra were built by Ricketts & Sons. His family lived in the same neighborhood as the Jones’. One of Albert’s daughters, Gwendolyn, was a member of the Palmyra High School graduating class of 1949, along with Clarence. Albert’s youngest son, Kenneth, who would eventually take over the business after his father’s death, graduated from PHS in 1954 as a fine athlete. Although Ricketts & Sons experienced racism, they were well-respected and integrated in the community. By the end of World War II, African American families in the “Village of West Palmyra,” like the Tunsells and Conwells, became business owners and members of the Board of Education.

Segregation was a fact of life in America prior to World War II and for many years afterwards. During Clarence’s childhood, primary education was segregated in New Jersey. Children in the Cinnaminson School District, which included Delran, Cinnaminson, Palmyra, Riverton and East Riverton, attended the Strabel School for White students and the Phillips School, a one-room schoolhouse for African-American students.

However, Palmyra High School had been integrated with affluent White families’ children attending school with their domestic servants’ children since the 1920s. This was an anomaly in New Jersey and also in the United States.

In 1943, two African American mothers in the Trenton School District would eventually sue the school district so that their children could attend a school designated for Whites. In 1944, they won their lawsuit, and integration began in New Jersey. It wouldn’t be until 1954 with Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, that segregation in schools was ruled to be unconstitutional. But at Palmyra High School, integration was already the norm. Because there was integration did not mean there was not racism or discrimination; in fact, there were certain rules that limited African American students’ opportunities and potential at the school. However, with the school’s integration history, by the 1940s, the number of African American students were increasing and the school was making headway in terms of reducing intolerance and racial tensions.

In 1943, two African American mothers in the Trenton School District would eventually sue the school district so that their children could attend a school designated for Whites. In 1944, they won their lawsuit, and integration began in New Jersey. It wouldn’t be until 1954 with Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, that segregation in schools was ruled to be unconstitutional. But at Palmyra High School, integration was already the norm. Because there was integration did not mean there was not racism or discrimination; in fact, there were certain rules that limited African American students’ opportunities and potential at the school. However, with the school’s integration history, by the 1940s, the number of African American students were increasing and the school was making headway in terms of reducing intolerance and racial tensions.

Palmyra was an older river town adjacent to Riverton on the south. The land once belonged to the Lenni Lenape Native Americans, but in 1689, the Swedes settled there and began building their homes. By the late 1800s and early 1900s, as the town progressed, the original farms’ outlying fields and lanes became building lots and streets. The coming of the railroad in 1834 marked the beginning of the gradual transition from agricultural dominance to urbanization. The Tacony-Palmyra Ferry opened in 1922. It made transportation to Philadelphia easier, thus increasing mobility of the residents and widening their horizons. The ferry was replaced by the bridge in 1929. During the Depression, the Work Progress Administration provided funds for improvements to the Borough, some of which were used to build the Palmyra High School Stadium in 1939.

The first school to serve Palmyra was constructed in 1822. After it was demolished in 1898, a one-room schoolhouse was built on Cinnaminson Avenue in 1865. This was the first to serve Palmyra alone. A second room was added in 1877, and a second story was constructed in 1886. Shortly after Palmyra separated from Cinnaminson in 1894, a new school was constructed. It was here that the first high school classes were held on a limited basis. The first class of the four-year program graduated in 1904. Eventually, in 1910, a new building of three stories was constructed on Delaware Avenue between Fourth and Fifth Streets. In 1922, an addition was constructed which included an auditorium and gymnasium. Until 1949, the year Clarence B. Jones graduated, the complex on Delaware Avenue contained classrooms for grades five through twelve.

Special mention should be made to the many successful teams that have represented Palmyra High School in sports competitions. Perhaps one of the most remarkable records in any sport was achieved by Matt Curtis who coached Palmyra track from 1941 through 1960: 19 straight Group II South Jersey titles, 15 Burlington County titles, and 9 Group II state championships. Curtis coached Clarence, who won medals at the 1949 Penn Relays.

Like the African American mothers who sued Trenton School District so their children could receive a good education, Mary had high expectations and aspirations for her young son. One day while visiting his mother, Clarence picks up a dirty dish to wash wanting to help her. Mary grabs the dish away from him and reprimands him. “The only thing I ever want to see you pick up, Son, is a pencil and a dollar!” Regardless of her situation, Mary had a vision for her son. In 1940, at the age of nine and heading to fourth grade, Mary decided to place young Clarence with the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament in Cornwells Heights, Pennsylvania, with whom she had also been placed as a young child after the death of her father.

The Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament was founded by Katharine Drexel of the banking Drexel family. Katharine’s uncle and mentor, Anthony J. Drexel, was the most influential financier of the nineteenth century and founder of Drexel University in Philadelphia.

Mother Katharine began her preparation for her role as foundress of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament in 1889. When she pronounced her vows of poverty, chastity, obedience and “to be the mother and servant of the Negro and Indian people” on February 12, 1891, she founded the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People. That year, the new community moved to Torresdale, to the former summer home of the Drexel family, while the motherhouse was being constructed in what was then Maud, later called Cornwells Heights and still later named Bensalem. In 1892, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament moved into their new home, opening as Holy Providence Home at that time, approximately 20 miles north of Philadelphia (less than ten miles from Palmyra).

Mother Katharine dedicated her life, time, money and energy totally to serving and educating Indian and Colored people. She was undertaking a work for which there was little popular support, even among many in the Roman Catholic Church. Mother Katharine enlisted the help of a small group of sisters who were quite young and lacked Mother Katharine’s experience and background, but she found them full of the love of God and zeal for salvation of the Indian and Colored races. They helped establish the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indian and Colored people; eventually there were 70 mission sites started across the United States by the time of Mother Katharine’s death in 1955, including Xavier University of Louisiana. Today Xavier is number one in producing African American graduates who become doctors.

By 1908, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament were teaching in Philadelphia at places like St. Peter Claver Catholic Church and Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament. Many years later, Clarence Benjamin Jones would eventually be baptized at Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament. Some of the children with the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament were orphans, but considerable efforts were made to ensure that the students left the institution prepared to be self-supporting.

Clarence found love, discipline and inspiration from the sisters at Holy Providence. In particular, a young sister from Ireland, Sister Mary Patricia, who had also worked with Clarence’s mother, took him under her wing. He received an outstanding education, learning Latin and excelling as a musician. Still, the sting of not living with his parents and not fully understanding why caused him sorrow. His infrequent visits with his parents during holidays and summers only left him more perplexed. But Mary was sure she had made the right decision during Clarence’s summer visit to the Jersey Shore after his first year with the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament.

Rushing back on his bicycle to the safety of his mother after being chased by a group of White boys at a seashore resort, a 10-year old Clarence runs into the kitchen of the summer home of his parents’ employer, crying, telling his mother that “White boys had chased him while riding his bike.” They had shouted names at him such as “nigger,” “jiggerboo,” “monkey,” and “sambo.” He is seeking the comfort and safety of his mother.

Much to his surprise, his mother sternly responds to him. She pulls him by the collar to stand before a mirror outside her kitchen door. Standing before the mirror, his mother asks him, “What do you see?” Still crying, he replies, “I see you, Mama. I see me.” His mother, unsatisfied with his answer, asks him again: “No. Tell me what you see.” Now, confused, he cries even more, and repeats what he said before: “I see you, Mama. I see me.”

His mother interrupts him, “No. What you see is YOU; the most beautiful thing that God has created. Pay no mind to what those White boys said. God created YOU. You are beautiful.”

That was powerful reinforcement to young Clarence’s self-esteem and self-image.

By 1935, Goldsborough and Mary were finally able to move into a home in East Riverton. At the age of 14, Clarence could no longer stay at Holy Providence. All high school age students were taken to Rock Castle in Virginia to continue their education. Instead he returned to New Jersey to live with his parents and was enrolled at Palmyra High School. Mary understood that Clarence would get the same education as the children she took care of, and he would finally be home with his family. Once at Palmyra High School, Clarence thrived and excelled. He was involved in numerous clubs and extracurricular activities, including band, orchestra (first clarinetist in the 1949 New Jersey All-State Orchestra), track (winning medals at the 1949 Penn Relays) and the National Honor Society. His senior year, he was voted “Most Likely To Succeed” and was selected as the Class of 1949 Valedictorian.

His proud parents sat in the audience for graduation as he delivered a speech captioned “Education For A Better World” that addressed breaking racial barriers. Tears flowed down Mary’s face uncontrollably watching her beloved Clarence fulfilling his purpose. For her, this was only one small step towards him reaching his divine destiny. Her Clarence would someday be a great man…that was her dream.

After graduation from Palmyra High in 1949, he received a four-year scholarship to attend Columbia College, Columbia University in New York. During his junior year, on January 8, 1952, his 21st birthday, while taking a midterm exam, Clarence received a troubling phone call from Cooper Hospital in Camden, New Jersey, giving him the worst news of his life. His mother was extremely ill with cancer and would have to have emergency surgery.

Although Clarence was conflicted, knowing that his mother would be upset if he missed school, he also knew his parents needed him, so he returned home. A weakened Mary pleaded with Clarence to return to school. Instead, he placed a desk at the foot of her bed so he could study and be near her at the same time. He periodically returned to college because she refused to believe that he had permission to stay home. She would cry, “Mama wants you to have an education. I’m going to get better. I’m going to get better.”

On May 4, 1952, Mary Elizabeth Jones died. While her emaciated body was being removed from the house, a distraught and inconsolable Clarence found a letter written to him by his mother asking Clarence’s forgiveness for leaving him. She expressed how proud he had made her feel and that no mother could ask for a son that could bring her greater joy. Along with writing the recipe for his favorite desserts, the letter concluded with, “I’m sorry to leave you, but I know that someday you’re going to be a great man. I know you’re going to be a great man.” With his mother as his inspiration, Clarence received his degree from Columbia University.

Unwillingly, he was drafted into the Army and served for a period of 21 months. He received an honorable discharge before heading to Boston University School of Law and receiving his law degree. He married in New York and headed out to California to pursue a career as an entertainment lawyer.

As America was confronting issues of racism and war on a scale that had never been encountered before, Palmyra became a beacon of optimism in 1959 when it appointed Payton “Tee Wee” Flournoy, Sr. as its new Chief of Police. Chief Flournoy was the first African American Police Chief in the nation. He had been an exceptional athlete at Palmyra High School, graduating in 1942, where he became the first African-American to be captain of the football and wrestling teams at Palmyra High School.

In February 1960, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., visited Dr. Jones in California and asked him to join the legal team that was defending Dr. King against a criminal indictment by the State of Alabama alleging tax evasion by Dr. King. As a consequence, Jones shortly thereafter, instead of continuing to pursue a law career in California, returned to New York with his pregnant wife and three young children and became a political advisor, personal lawyer and draft speechwriter for Dr. King.

As Dr. King’s attorney, his assistance during the “Civil Rights Movement” would end American “Apartheid” and transform the United States of America.

In November 1962, Dr. Jones’ father Goldsborough died. His funeral service was held at Mt. Zion AME Church in Riverton on Penn Street. Mt. Zion AME, a minuscule church in size, was built in 1909 for the African American community of domestic servants that lived in Riverton. While waiting for the service to begin, the minister informed Dr. Jones that Martin Luther King had arrived and wanted to say a few words publicly. The grief-stricken son was somewhat dumbstruck. Martin Luther King? How did Martin Luther King know where he was and why had he come? Dr. King had never met Dr. Jones’ father but was led to the altar.

Finally, standing at the raised pulpit with an open casket below, Reverend Martin Luther King began, “I know my friend Clarence Jones is probably surprised that I’m here. I did not know the deceased, his father, Goldsborough Benjamin Jones, but I know his son.” Leaning over the pulpit and looking into the casket at Goldsborough, King began preaching directly to Dr. Jones’ father, “Brother Goldsborough, I did not have the privilege to know you, but I know your son.” He continued his oration with beautiful expressions of comfort, concluding “You can rest and go home, because your son…” He then filled the small church with eloquent praises of Dr. Jones.

Overcome with emotion and still confused about how Martin Luther King had discovered his father’s funeral, Dr. Jones was inconsolable. As covertly as he had arrived, Dr. King left after making his comments. No autographs. No salutations. He just left. That memory would remain one of the most cherished and unforgettable experiences of Dr. Jones’ relationship with Dr. King. Dr. Jones’ father, a domestic servant, considered inferior by many in America based solely on his skin color, was given a royal farewell. A small Black church built for domestic servants of affluent white residents of Riverton, New Jersey, located in the middle of elite, exclusive clubs and estate homes, during the most racially-charged period in American history was a trope for the ridiculousness of racism.

In 1963, a few months after Dr. King attended the funeral of Dr. Jones’ father, while still grieving his father’s death, Dr. Jones played a major role in the Civil Rights Movement.

In April, Dr. King is arrested and imprisoned in an Alabama jail. While there someone smuggled in a newspaper which contained a statement made by eight white Alabama clergymen against King and his methods of nonviolent resistance against racism. This agitated King and he writes a response in the margins of the newspaper itself, using scraps of toilet tissue and writing paper supplied by Jones who would then deliver the message to the civil rights headquarters.  Later these writings were published as “Letter from Birmingham City Jail.”

Later these writings were published as “Letter from Birmingham City Jail.”

Later Jones helped organize what many consider to be the largest Civil Rights protest in the history of the United States, the “March on Washington For Jobs and Freedom.” Not only was Dr. Jones fundamental in the organizing and strategizing of the March, but also he assisted Dr. Martin Luther King in writing his “I Have A Dream” speech.

During the delivery of the speech, into a few paragraphs of prepared text suggested and constructed by Dr. Jones, Martin Luther King, Jr., puts the written speech aside and begins to share his vision for America. It was a dream he had shared with a few intimate friends, but now the world would be inspired with what would become one of the most powerful and inspiring speeches, not only in the United States, but across the world.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream… I have a dream that one day in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right here in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”

With those words, Martin Luther King expressed the vision of millions of disenfranchised and marginalized people of color in the United States who had the same aspirations and dreams as their White brothers and sisters but didn’t have a voice. Finally, African American parents wanting the best for their children, wanting a future in which their children could reach their full potential and achieve their dreams, felt their cries were heard. Mother Katharine and the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament had the same dream.

For Clarence B. Jones, he had experienced, to a degree, what that could look like while with the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament and during his years at Palmyra High School. Clarence’s mother Mary definitely shared Dr. Martin Luther King’s dream before it was spoken and heard by millions of Americans. Her dream wasn’t blurred or obstructed by her discriminative and oppressive status in America. Her focus was only on the unlimited potential of her young, beloved Clarence.

Although she was not able to hear the words her son had penned for Martin Luther King or witness Clarence become the man she had envisioned — cashing the promissory note that the United States had written to every American with the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence that stated that all men would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness — her dreams for him would survive her death. She refused to believe that “the bank of justice is bankrupt,” and her spirit guided him and inspired him. Mary’s young Clarence became the man that wrote those words and honored her legacy by being an icon of the Civil Rights Movement.

At age 36, Jones becomes the first African-American to be named an allied member of the New York Stock Exchange after joining an investment banking and brokerage firm of Carter, Berlind & Weill where he worked alongside future Citigroup Chairman and CEO, Sanford I. Weill and Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman, Arthur Levitt.

On April 4, 1968 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis Tennessee sending shock waves around the world. For King’s close associates and friends, including Dr. Jones, although shocking, this was not a surprise. They always believed it was not a matter of if King would be assassinated but when he would be assassinated. “Martin was afraid, personally afraid but fearless” is how Jones remembers Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

On October 1, 2000, Mother Katharine was formally canonized in Rome during the great Jubilee Year making her the second recognized American-born saint. The two miracles needed for the process of Mother Katharine’s canonization involved restoring the hearing of two children. Like Martin Luther King, Jr., Saint Katharine is an advocate for listening to the cry of those in need. She listened to the needs of those underserved in so many areas, those deprived of a good education or health care, and those not introduced to the Catholic faith. In turn, Saint Katharine asked the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament to listen to the needs of their students and to encourage their students to become leaders. Even in her 80s, she saw the leader in young Clarence as he attended mass as an altar boy while sitting in her wheelchair after suffering a serious illness. Dr. Clarence B. Jones has certainly fulfilled that dream.

In honoring Martin Luther King Jr., Dr. Jones has written two books about Kings’ philosophy, legacy, importance and dream. What Would Martin Say? and Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation, Jones provides an intimate look at Martin Luther Jr.

In honoring Martin Luther King Jr., Dr. Jones has written two books about Kings’ philosophy, legacy, importance and dream. What Would Martin Say? and Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation, Jones provides an intimate look at Martin Luther Jr.

In 2015, President Barack Obama honored Dr. Clarence B. Jones at the White House.

In June 2017, after nearly 70 years, Clarence Benjamin Jones, a distinguished Palmyra High School alumnus, returned home to be welcomed back and honored. The Palmyra High School library was named the “Clarence B. Jones Library,” the Borough of Palmyra gave him a key to the town and the Dr. Clarence B. Jones Institute for Social Advocacy was established. He also made an emotional visit to the campus of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. A few months later the property was sold.

The recently formed Dr. Clarence B. Jones Institute for Social Advocacy is another example of an innovative educational and social tool aimed to enhance the educational experience of students. Its mission is developing and preparing leaders who know how to serve the public through civic engagement, social advocacy and community service. The Institute follows Dr. Jones’ example.

Family is Key. Dr. Jones’ parents were his foundation. We must support our children and encourage them to dream big dreams.

Education is Key. We must invest in our schools. An investment of a good education, for all children, has an unlimited return.

Community is Key. It takes a village to raise a child; whether with the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament or in the Palmyra-Riverton community, or with each loving home he was placed in, Clarence was nurtured and loved. We should all be “parents” to children in our community.

Soul-to-Soul Relationship is Key. We must recognize and understand that when we treat each other with respect, love and honor without prejudices, bias and discrimination, only then can we all reach our full potential and join together in Dr. Martin Luther King’s dream.

One of Dr. Jones favorite quotes is from St. Augustine of Hippo who said: “Hope has two beautiful daughters; their names are Anger and Courage. Anger at the way things are, and Courage to see that they do not remain as they are.” Dr. Jones’ philosophy is that we are all trustees for our children “Anger” and “Hope” and our fiduciary duty requires us to protect and safeguard them; encouraging the eternal longevity of “Anger “and “Hope.”

We must never forget the redeeming POWER of Love. The legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King teaches us that ONLY love can enable forgiveness, redemption and reconciliation, pre-conditions for non-violence. Saint Katharine believed each person was called by God to be a saint. “Love is proven by little things. Great things may never be asked of us.”

According to Dr. Jones, “The fierce urgency of now,” (Dr. King’s words from his “I Have A Dream” speech), is how can WE inspire a younger generation to understand the personal gratification and self-empowerment that can come from the pursuit of educational excellence? To encourage “the pursuit of excellence,” we should heed the advice of Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.”

In Dr. Jones’ latest book, Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation, he gives his secret for change. “Change can happen. If you truly take that to heart, almost without noticing or choosing so, you’ll find you are the one helping make the change.”

Now, at the age of 87, an Adjunct Professor at the College of Arts and Science, University of San Francisco, and Scholar in Residence, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, Stanford University. He is also in the final phase of writing his memoirs.

Palmyra, New Jersey 08065

Palmyra, New Jersey 08065 (856) 220-6298

(856) 220-6298